Fri 10 Aug 2007

Quebec has a rather strange history when it comes to poets who are more or less linked with Modernism, at least among the menfolk.

Claude Gauvreau, for instance, associated with the group of Automatiste artists such as Paul-Emile Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, wrote several theatrical works usually considered as extreme as Artaud’s, and yet he jumped (or fell) off a building in 1971, and had been hospitalized ten times for psychological disorders prior to that. Two books of his have been translated by Ray Ellenwood — Entrails and The Charge of the Expormidable Moose — and Steve McCaffery has a nice essay on his poetry in North of Intention. Wikipedia has an English-language biography.

Hector de Saint-Denys Garneau is usually considered the first truly modern Quebec poet, and despite being rather good-looking, he died of a heart attack while canoeing in 1943 at the age of 31. He also has a Wikipedia biography. I’ve enjoyed reading his poems in translation, and he seems to be popular enough with the young Quebec crowd to have inspired a short video based on one of his poems which appears on YouTube. Most videos based on poems seem to be pretty bad, but this one fares reasonably well despite some hammy acting.

Next to lastly is Sylvain Garneau, no relation to the above poet, who wrote mostly rhyming verse in quatrains and other forms. His work comes across remarkably well in translation, sounding a bit like a cross between Brecht of Die Dreigroschenopfer and Jacques Brel. There’s no complete English-language edition of his work, which inspires me to give it a shot myself, since I love Brecht and Brel. Also apparently a dashing fellow (I’ll let you be the judge — at least he dressed well), he committed suicide at the age of 23 in 1953. The Canadian Encyclopedia has a good biography of him, as they do of the other poets mentioned here.

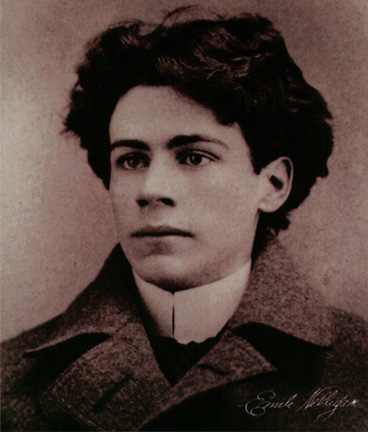

Before all of these blokes, however, was the poet Emile Nelligan, who lived to the ripe age of 62 but was hospitalized at 19 for what appears to be schizophrenia and wrote nearly nothing afterwards, living out his days in the asylum in near total indifference to the world. Born in 1879, he read widely in French Symbolist literature, especially Baudelaire and Verlaine and two poets I know nothing about, Rodenbach and Rollinat. He might have read Rimbaud, but it’s not clear given the availability of the literature in Quebec and Rimbaud’s unusual publishing history.

Anyway, I sort of “discovered” Nelligan during my last year at college while on a trip to Quebec City with my family. I walked into a bookstore looking for the “Canadian Rimbaud” — since I have a pet theory that every country has their Rimbaud, troubled adolescent genius who wrote their entire works before the age of 20 or so, and I was obsessed with Rimbaud at the time — and saw Nelligan’s photograph and bust (the bookstore was selling small plaster statues of him) and knew instantly, without looking at the books or reading a bio, that this was him. I think it’s because his photograph reminded me of the famous photographs of Rimbaud during his “seer” phase in Paris which you’ve all seen.

Turned out to be sort of true — Nelligan wasn’t nearly as original as Rimbaud, but he was a “visionary,” and he still seems to be the central point of inspiration for many Quebec poets wanting to push the boundaries. I ended up translating four of Nelligan’s poems for my senior project at Bard, two of which appear below (I got the other two very wrong in places, I don’t know French all that well). They may seem a little olde fashioned but I think they still hold up. There’s a really nice selection of translations available by P.F. Widdows, and a more awkward but readable complete edition by Fred Cogswell.

(Nelligan has a huge hotel in Montreal named after him; Sylvain Garneau has a library. Walt Whitman has a rest stop — just like Joyce Kilmer!)

You’ll notice — those of you who read or speak French — that I use some rather literal word choices, for example “massive” for “massif,” which would not really be accurate translations. I did this on purpose since I like to use the original language in a translation to “deterritorialize” or render strange the English of the new poem. Also, Nelligan fans, you’ll notice that the “ideal ocean” in the original is where hurricanes don’t swirl, but having that Rimbaud itch, I made the waters rather torrential.

Petition

from Emile Nelligan

Queen, will you assent to unfurl just one curl,

One billow of your hair for the blades of scissors?

I want to inhale just one note of the birdsong

Of this night of love, born from your eyes of pearl.

My heart’s bouquet, trills of its thicket,

In there your spirit plays its roseate flute.

Queen, will you assent to unfurl just one curl,

One billow of your hair for the blades of scissors?

Silken flowers, perfumes of roses, lilies,

I want to return them with a secret envelope.

They were in Eden. One day we’ll take ship

On the ideal ocean, where the hurricane swirls!

Queen, will you assent to unfurl just one curl?

The Ship of Gold

from Emile Nelligan

There was a mighty ship carved of massive gold:

Its masts touched the azure, on the unknown seas;

The Cyprus of love, hair loose, with nude torso

Stretched herself on its prows, in excessive suns.

One night, however, there came the great danger

In those clever oceans where the Sirens sing;

This horrible shipwreck inclined the ship’s bottom

Toward the depths of the abyss, unchanging grave.

There was a ship of gold, and its diaphanous flanks

Displayed its rich hold to those profane sailors,

Disgust, Hate, and Nerves… they split it between them.

What is left of the ship from that so brief Tempest?

What has my heart become, but a deserted ship?

Alas! it has foundered on the vacuum of the dream.

August 10th, 2007 at 12:18 pm

this is great — thank you.

November 28th, 2007 at 8:33 pm

Your translations are actually very well done. I am doing a report on him because I believe him to be a great poet. Do you know any information about him before he had his first poem published? Why did he become a poet? Did anyone help him? How is he different from other poets? How has he affected the literary world?…And so on and so forth. Thank you and please write back with any extra information!

November 30th, 2007 at 1:49 pm

There’s tons of information about Nelligan online so I won’t recount it here. But I can say that he still considered one of Montreal’s greatest poets, and his influence, and perhaps his example, has been very strong. Look up the other poets I mention in the post as well, some of them had a similar outlook.

March 23rd, 2009 at 1:12 am

I am descended from the Nelligan families (Ireland-Kilderry) I was quite amazing to discover Emile’s exquisite poetry on the web.

He expresses all that yearning visionaries display – his poetry seems more french Rimbaud

How would he fare today I wonder? Would his country favour and nourish his genius?

his intensity is so palpable, it seems to burst from his and fly into the ether without having any kind of earthing – The phrases are so fragile, like glass flowers broken in careless hands. I thank you from bringing Emile into my home and heart.

August 10th, 2012 at 4:58 pm

The English translation of “Le vaisseau d’or” is quite accurate. Nelligan left us a few poems that were harbingers of what was to become of him.”Le vaisseau d’or” is one of them. So is the poem “Soir dhiver”, a real jewel of alliteration or more accurately of what we call “harmonie imitative”. The shivers of winter are clearly felt, not only of winter but also of

inner anguish.