Sun 4 Oct 2015

Dear New Yorker,

I’m writing to you concerning the racism of the 6,000-word profile of Kenny Goldsmith titled “Something Borrowed.â€

The racism expresses itself structurally: understanding that some readers will already be aware of the controversy around Kenny’s work, and that those unaware might be turned off when it’s revealed that Kenny is “beleaguered†due to the uproar around his reading of Michael Brown’s autopsy report – revised to end, consequently, with a note on the “unremarkable” nature of Brown’s genitals – as a piece of “avant-garde†art at an Ivy League arts conference, the author sets the stage for a sympathetic reading of this obscenity by demonizing those who would critique it. The author seeds the text with subtle denigrations, largely through negative characterizations, of non-“conceptual†writers, targeting particularly Asian Americans.

The first seed: in paragraph three, the poet Cathy Park Hong is noted as speaking “resentfully†about Kenny’s career. The quote from Hong is neutral (“He’s received more attention lately than any other living poetâ€) and is not characteristic of Hong’s thinking as expressed in several recent articles – that is, anyone could have said it. The only reason this sentence exists is for the final adjective: resentfully. The author could have quoted any of the established older white (male) poets who are brought in later in the essay like C. K. Williams, Charles Simic or Dan Chiasson, familiar to readers of the New Yorker, to serve as a hook for, or easing into, the article. Instead, he chose the relatively obscure female poet with the Asian name to set up the big reveal. Hong is depicted, if slyly, as barbarian No. 1.

About 3,748 words into the essay (a little over halfway), no mention yet being made of the Michael Brown piece (“beleaguered†floats as an indeterminate tease), this remarkable sequence appears:

Goldsmith’s hegemony as a conceptual poet… has led a number of other conceptual poets to feel that he monopolizes a territory that excludes them. Many of these writers identify themselves as poets of color. A poet named Tan Lin wrote me, “The conceptual program, as it has been developed and codified by critics in the past ten years or so, and I am really talking about the institutionalization of conceptual poetry in academia, has focused mainly on the work of white authors.†Dorothy Wang, a professor at Williams, said that poets of color have grown “pissed off by the stranglehold white people have on avant-garde poetry.â€

This is a classic non-sequitur; what prompts the entry, after the first sentence, of “poets of color”? Why have the white conceptual poets been excluded form this set of “other conceptual poets” of whom the huge majority, lets say 99%, are white? Tan Lin is, indeed, a poet of color – he’s Maya Lin’s brother – but one could hardly identify him as an identity writer, nor does anyone consider him a “conceptual poet†in any of the ways described in the article. The quote from Lin, consequently, doesn’t even mention Kenny or hegemony – Lin even qualifies his statement by noting that he is speaking of “critics†and “academia.†Dorothy Wang, on the other hand, is not a poet at all – she’s a scholar.

The adjective “many†is used to describe a mere two, and “of color†simply to describe Asian Americans. How did this get past the editor (presuming the editor wasn’t Donald Trump)? The writer suggests that black, brown and yellow hordes are storming the barricades in a thrust against “hegemony†but in fact, in this article, the hordes, like Trump’s murderous Mexican rapists, never appear. (Tellingly, the author, like Trump, merely pivots to scapegoat Asians.)

If Wang is being brought in to vouch for the poets of color making this argument about the “avant-garde†– which is also not synonymous with Kenny or conceptual writing – Hong’s own words could have been employed here since she inaugurated this argument in her controversial polemic, “The Delusions of Whiteness in the Avant-Garde†which appeared in the journal Lana Turner nearly a year ago and is readily available on the web. Any journalist with integrity would have tried to trace at least one more of these “many†writers down. Lin and Wang are barbarians No. 2 and 3.

But the sheer ill will – I have to call it racism – doesn’t stop there. Your author continues:

Some poets of color feel that Goldsmith is subtly denying selves that they wish to assert and explore. Only a white person, these writers say, has the ability to shed his or her identity or to wear it casually. Their experience is that to be a person of color in America is to be constantly reminded of who you are. Dorothy Wang feels that identity in conceptual poetry “is a code word for racial or ethnic identity.†She says, “Often, the assumption is that good experimental avant-garde work is bereft of identity markers, and that lead-footed, autobiographical, woe-is-me, victim poetry is minority poetry.â€

We still don’t know who the hell are “these writers†are? Of the two mentioned, Tan Lin could hardly be said to be wishing “to assert and explore†his “self.†Lin writes in Seven Controlled Vocabularies, an exploration of “ambient†poetics: “A poem or painting or landscape is beautiful at the moment it is forgotten, when it subtly accentuates a style or mood without drawing attention to itself, like drapes or a shade of paint.†This is hardly the battle cry of an ethnic essentialist; Lin has read his Kant, and is well aware that the “self†is a tricky thing. Once again, Dorothy Wang – not a poet – is brought in as somehow representative, this time not of the “many†but of the “some.â€

At this point, not a single black or Latino author has yet been mentioned (which is to say, employed like pawns in this sophistic circle jerk). African American poet Tracie Morris (brought in at around word 5,468) is situated as one of the “few†to defend him, while Mónica de la Torre is permitted to offer something like a distinctive, nuanced comment – “The problem is that both positions are equally flawed†– that spares her, like Morris and unlike the resentful Hong, from being a barbarian. Morris and de la Torre are brought in after the big reveal, in fact, to somehow help mollify (if unwittingly) the obscenity of Kenny’s reading at Brown University.

A general argument is proposed: Kenny’s Michael Brown piece illustrates that there is only a narrow, worthless discourse – or perhaps a compelling ethical dilemma – concerning who is able to “speak for people who have been harmed or who have suffered.†The trick is that entering into this debate will always result in the conclusion that Kenny’s piece worked, even if in Mephistophelean ways, for the cause of “good.†Art, unlike, say, a train bombing, can always in retrospect be considered a goad to greater understanding even if it “hurt†the people who first witnessed it. A rabbit hole opens leading not to nowhere, but to the canonization of Kenny’s piece in the inevitable tomes devoted to the major events of 21st century “poetry.†(The travails of this journey are alleviated because, in this article, the barbarians have already been depicted as classic philistines, “politically correct†Jihadists with no understanding of this Faustian gamble.)

Fine.

The real issue with Kenny’s Michael Brown piece, to my mind, is the general awfulness of Kenny’s artistic production, including the lameness of his public persona, over the period of time since that Buffalo conference. It’s this very awfulness that he took into the auditorium at Brown University in his attempt to perform (he claims) an elegy – he was really just trying to revive the Kenny G brand – for the person about whom several thousand people had just rioted and rebelled.

Take one example: Kenny’s book Head Citations from 2002, an “irreverent and amusing collection [that] consists of over 800 ‘misheard’ song lyrics†according to the press release, was merely a recycling of the method of ‘Scuse Me While I Kiss This Guy: And Other Misheard Lyrics by Gavin Edwards, a novelty book published 1995 by Touchstone Books. It would take quite a mental acrobat to link the monastic integrity of Sol Lewitt’s “Sentences on Conceptual Art†to this juvenile bauble. I’ve heard Kenny read from this several times and it always struck me as incredibly dumb, not to mention cloying. Nonetheless, like Seven Deaths and Disasters (which I thought Colbert had lethally exposed as a mere stunt) and potentially the Michael Brown piece were it to have been published (“the eighth American disasterâ€), it makes for a perfect MoMA stocking stuffer.

Another example: anyone who’s heard the Kenny reading at the White House (available on YouTube) can hear that he really doesn’t know how to read poetry. He massacres the bits by Walt Whitman and Hart Crane (used to set up Traffic) with that smarmy, shit-eating Adam-Sandler-meets-William-F.-Buckley voice that was so potent and fun on his radio show for WFMU but couldn’t be banished enough for occasions requiring some gravity (which no doubt contributed to the awfulness of the Michael Brown reading, the audio and video of which, as your author mentions but with different verbiage, Kenny suppressed.)

Kenny never read even his best work (such as No. 111) very well; now that he’s added salmon-colored shirts, mismatched socks and a Tolstoyan beard to his product, the impression is that artistic integrity has long since departed, any note of “critique†being replaced by simple market logic. (For what it’s worth, I’m not alone in this opinion: many of my poet friends – and, yes, white friends, not only your enfeebled “poets of color†– have been embarrassed for Kenny by this turn of his toward outright charlantry.)

A final example: it’s noted around word 5,567 that “Goldsmith makes a substantial part of his living from readings, and over the summer he was concerned that fewer places would hire him.†This occurs after the unusually long note on his familial heritage. Kenny’s lived, for as long as I’ve known him, in a huge, at least 6,000-square-foot apartment (I don’t know anything about real estate and my eyes are bad – this is a wild guess) in Manhattan in the 20’s between 5th and 6th Avenues (I think his parents bought it for him after graduating RISD). His only other income, from what I know, is from his lecturer position at U Penn. But even if Kenny lived in a broom closet or fish bowl in Chattanooga, how much cash could Kenny possibly draw from the poetry reading circuit – a not particularly flush segment of the civic population – to make a “substantial part of his living� Does he subsist on water, oats and Chef-Boyardee?

“Before Goldsmith became a poet, he was a text artist,†your author writes. Though he might play one on TV, Kenny is not a poet. Kenny doesn’t even like poetry (bravo that he’s read Ulysses several times; and Chris Christie has never missed a Bruce Springsteen concert) and has always been disdainful of poets. (It’s a weird irony that the Language poets wished to be known as “Language writers†and yet are not, while conceptual writers are being called “conceptual poets†despite, on the part of some, their overt hostility to the art – marketing is certainly everything.) I can accept that some of Kenny’s work itself is poetry, but Kenny is a poet in the way that a person who has fallen down the stairs – in the meantime exploring, if unwittingly, some unique, compelling human configurations, the cell phone video having received a million hits on YouTube – can be called a dancer or choreographer. (Insert Chevy Chase reference here.)

But my concern isn’t with Kenny, to whom I wish the best. I’ve known him personally for some time, even contributing material to ubu.com back in the day, though I withdrew from any communication with him years ago (largely because of his insufferable ego and terrible ideas about art). I’d like to say that the author of “Something Borrowed,†Alec Wilkinson, was well intentioned – but I can’t. Wilkinson, better known (I believe) as a music critic, has no doubt been an admirer of Kenny since Kenny’s days as a music critic for the New York Press back in the 90s – “bromance†is written all over this article.

No Seymour Hirsch, Wilkinson seems willing to publish whatever garbage Kenny fed him, including inventing a new origin myth, necessary for any proper hagiography, revolving around some clandestine meeting in a bar in Buffalo, which is pure horseshit (I was there, and know all the actors well). I’m also sure that it was Wilkinson who, clever man, threaded his article with such subtle, but clearly potent, racism to frame Kenny’s catastrophe in the best light. Wilkinson’s list of barbarians eventually grows to include CA Conrad (who if anyone could expose Kenny’s claims to be an “outlaw†as pure narcissism), Ken Chen (Asian American!) and the self-styled Mongrel Coalition (no fans of mine, by the way), quoting from one of their scattershot tracts. These poets are depicted as unfortunate victims of their own misunderstanding of the purity of Kenny’s desire to “provoke†in the name of the “avant-garde,†of the obsolescence of the discourse on ethnic identity, and of a narrow conception of poetic form, human creativity and the ubiquity of algorithmic culture (lyricists “allergic†to procedural poetics).

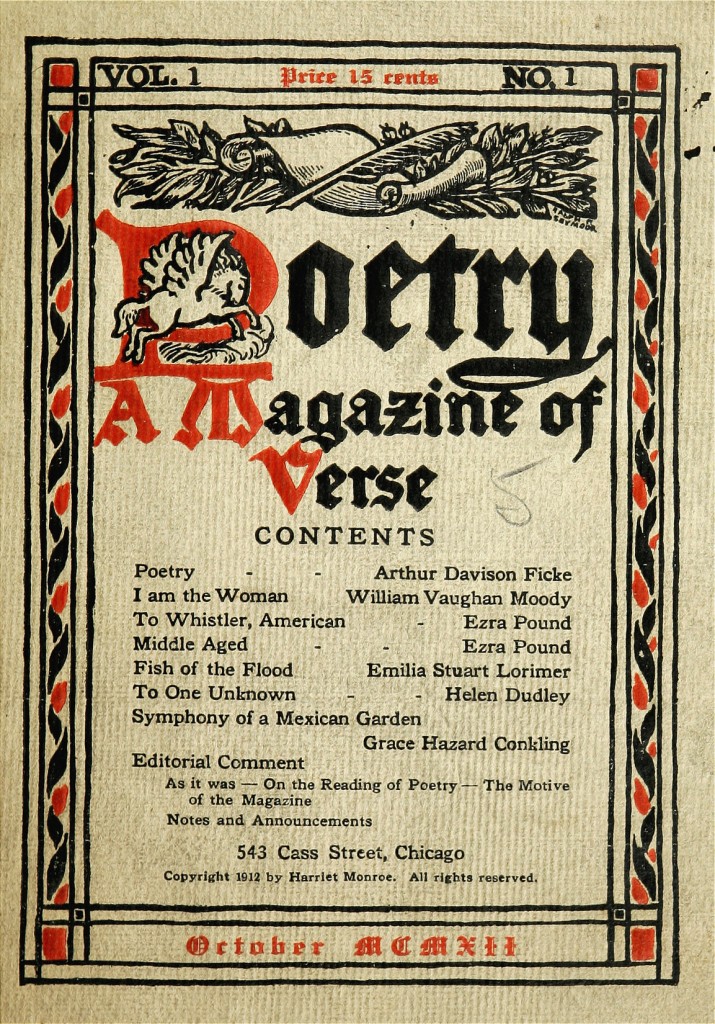

As much as Kenny would like to figure himself as the extension of tradition of Mallarmé, Beckett, Cage, Warhol and others, one would have to ask: when did the “avant-garde†tradition make it their business to target minorities? (Granted, in this tradition, anti-semitism and the exploitation of African art was commonplace, but this, I presume, is not the tradition Kenny or his supporters are identifying with; pictures of Pound, Eliot or Celine do not appear on ubu.com.) When did it become the job of the enlightened “avant-garde†artist to fuck with the minds of people of color (and not their classic targets, the bourgeoisie)?

André Breton, one of the greatest provocateurs in the history of art, went to Haiti and endorsed the first publications of the Négritude in a sincere effort to encourage political change, to foment revolution, to transform the social order – now it’s the job of white artists to play vicious pranks on minorities for the mere sake of continuing a tradition, or just as something to do? Kenny G states: “I’m an avant-gardist. I want to cause trouble, but I don’t want to cause too much trouble. I want it to be playful.†That’s the artistic platform one takes into “appropriating” Michael Brown’s autopsy report?

(As a side note: no negative comments by black authors are recorded in Wilkinson’s article, even as they proliferated on the internet in the wake of the reading. John Keene is particularly notable in this regard in his writing on “the limit point of certain conceptual aesthetics.†This is mere cowardice: Wilkinson was quite aware that any screw-up by the New Yorker concerning African Americans would lead to a backlash from several quarters and puncture any possibility of redemption in the profile, whereas a backlash by Asian American writers has been traditionally easy to brush off as an extreme form of “identity politics.†The solution – to simply exclude black writers from a discussion of Michael Brown – is telling of how much he hoped to get away with.)

I’m far from a moralist when it comes to art, and I’ve tried as much as anyone to create an “expanded†notion of poetry, but the perversion of values in this article is nauseating. Who was this article written for? Are we actually back in the 80s? Is this Pee-wee’s Playhouse?

Wilkinson notes that Kenny “was paid five hundred dollars for his reading, and he gave the money to Hands Up United, an organization that called, among other things, for an investigation of Michael Brown’s death.†It’s the definition of corporate shilling when a journalist uncritically repeats Kenny’s attempt at damage control – think of the Vatican giving money to victims of sexual abuse for the sake of the press – to massage away the reality of his utter nihilism. Did Wilkinson ever humor the idea that Kenny, who has never exhibited any concern with social issues in his work or person, might have been insincere? (And is Kenny really making a living giving $500 readings?)

Wilkinson seems quite happy to have shoveled whatever pabulum Kenny sent his way and cut-and-pasted it into his article. “My books are so boring that even the copy editors can’t read them,†he claims that Kenny “said recently†– this has been a pretty common line of Kenny’s for years in interviews. As for common sense: does Wilkinson really believe that any of Kenny’s works had copy editors? Absurd formulations that have long moldered – “The modernist project… had always been to deconstruct language to its smallest shard… [L]anguage got so atomized that there was nothing left to do†– are given new life in Wilkinson’s blinkered attempt to write a compelling art hero into existence for the New Yorker, one who is, as if to order, both transgressor and victim.

But Kenny is not the victim. The proof is right there in the article. Perhaps the most revealing passage occurs around word 3,972, just before the big reveal, when Wilkinson writes:

Flogging this conceit [of being an uncreative writer], however, had led to conceptual poetry’s being regarded as unfeeling and as interested only in formal problems. The perception that the field had discovered its boundary had led to its being less well attended. “We held the stage for fifteen years as the most challenging movement in poetics, with a form of expression that many people hated,†he said. He wanted to hold the stage a bit longer.

What would help, he thought, was to find “a hot text.â€

This would almost have been a redemptive passage – laying bare the machinations of Kenny’s carpet bagging, imperialist mentality – but one misses the saucy, editorializing adverbs Wilkinson favored in his quote from Hong. How about:

After “Sports†he “got bored with being boring,†Goldsmith said banally. His work had traced “a trajectory that starts with the driest copying, where I trumpet being the most uncreative writer on the planet,†he said megalomaniacally. “We held the stage for fifteen years as the most challenging movement in poetics,†he said blindly. What would help, he thought delusionally, was to find “a hot text.â€

Wilkinson also decided not to mention what every follower of this controversy has long known, that the notion of the conceptual “hot text†had already been broached by Vanessa Place, a writer (and self-styled Mephistophelean) who had used, for example, the “statements of fact†that she wrote defending sexual offenders in her day job as a lawyer (published as a book in 2010). Place has also been also recently been embroiled in accusations of racism for a project in which she republished the text of Margeret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind in 140-character tweets, using for her profile photograph a picture of black “nanny†and a “coon†drawing of the period, a project she claims is overtly anti-racist but which others have understood as akin to the exploitation in Kenny’s Michael Brown piece.

Kenny was, no doubt, emboldened by Place’s Statement of Facts. But Kenny’s (or Wilkinson’s) claim that conceptual writing was moving beyond merely “formal problems†with Seven Deaths and Disasters is completely wrong: that book, and the Michael Brown piece, was a testing of the properties of conceptual writing on intractable material that would inevitably create a stir but in which the artist had no investment. To that extent, the Michael Brown piece was paradigmatically a formal experiment: how to take the act of plagiarism and “give it legs,†in journalistic parlance, in a time in which the conceptual writing brand (or Kenny’s career) was growing thin. Wilkinson’s note about the hubris of “wanting to hold the stage a bit longer†doesn’t approach the monstrosity of the means of doing so: invading a territory to extend or expand the life of an artistic prospect or career regardless of who actually occupied that territory (or who else made art concerning Michael Brown), a sort of Lebensraum philosophy of maintaining and expanding an individual’s cultural capital.

There is no reason a white artist can’t make compelling, disturbing art concerning Michael Brown’s death. There are many reasons why this shouldn’t be done merely to test a product, illustrate the robustness of the “avant-garde†tradition or revive interest in a flagging (white) artist’s career, especially with the legacy of sheer buffoonery that had characterized Kenny’s career to that point. Imagine “Weird Al†Yankovic publishing a funny song about Whitney Houston’s death, claiming (after suppressing the song and donating his earnings to charity) that he had been simply tired of the “Weird Al†formula and wanted to test it:

His phone rang, and it was Marjorie Perloff, telling him to ignore a spiteful post that had appeared that morning. Weird Al paced as he talked to her. When he sat down again, his face looked drawn. “Sometimes I think I might be headed back to the world of novelty recordings and Dr. Demento,†Weird Al said ruefully. “I don’t deny that possibility. They still seem to like me there.â€

Poor baby.

The kind of people who think it’s cool to take the SAT’s on acid because they’d “already deconstructed and critiqued the culture†are not the same people who protested the shooting of Michael Brown. If Brown (whose high school graduation photo was projected as the backdrop to Kenny’s piece) had taken the SAT’s on acid (yuck yuck yuck), he would have been caught, then safely ensconced in a prison somewhere on August 9, 2014, and would not have been shot on the streets of Ferguson for shoplifting cigarillos. Nothing of his life would have been available for recycling or exploitation by an “avant-garde†artist, even a good one. After release, Brown would have been burdened for the rest of his life with a prison record limiting his job prospects, no higher education at 25, most likely a despairing attitude and the poverty from which he and his family had already suffered. The thought of making a career change by turning to republishing “boring†or controversial texts for the tourists and art groupies who shop in the MoMA gift shop couldn’t have crossed his mind.

I’m sure the pages of the New Yorker have gushed on occasion with some remorse for the persistence of racism in the United States and for the “tragedy†of Michael Brown. In that case, the presence of this article points to a raging hypocrisy among your editors and readers. But I am a barbarian; I am most likely missing something. Perhaps remorse for Michael Brown’s death, a condescending and scapegoating attitude toward Asian Americans and all writers of color, and the need to bolster an individual’s flagging artistic career regardless of the value of his work (so long as it sells copies and confirms the elitist tradition depicted on the famous 1925 cover reproduced above) are all non-contradictory in some elevated – and eternally elusive to the hoi polloi – world of ideal forms, in which case 2+2=5.

Brian Kim Stefans is a poet and Associate Professor of English at UCLA.