|

The new image is of Madame Sosostris... but those are not Iraqi playing cards she's dealing.

Here's a site run by autonomedia.org and interactivist.net with writing by Stewart Home, Terry Eagleton, Antonio Negri, etc. I'm pasting in the first paragraph of a book review by Stewart Home below since it seems to have something to do with what Darren and I have been talking about regarding "writing" and the multi-authored blog, etc. Compare Home's ideas to some of what is happening on Silliman's site -- I'm sure that RS would agree with what is by now a truism regarding the bourgeois subject and "style," but my sense is that the cult of style -- as much as RS is positioning himself against the "school of quietude" -- is very much alive in his critical vocabulary; certainly no Language poet has gone as far in the critique of the bourgeois subject as the Situationists and their kin have. For the most part, I've never had any problem with the "bourgeois subject," at least some varieties, as it's been so long since we've seen anything else that I think even the most "radical" among us are more or less bourgeois (and the most un-bourgeois tend toward the side of religious fanaticism, even of a secular sort, but there are fewer of them in the art world). I kind of think of Andy Levy as probably the most obvious example of someone redolent of the aura of hearth and home but more or less affecting a "radical" open style, but much Language poetry is somewhat infused with the hankering after "style" and whatnot. My sense is that many writers who dismiss "style" as a bourgeois tick have simply never been able to acquire a style worth preserving -- it's not easy to do -- and are often readable, even compelling, but ultimately bland (dare I say anemic? winky winky) writers. But as James Schuyler once said, if we're not bourgeois, what are we?

Interactivist Info Exchange: Independent Media & Analysis

The Return of Proletarian Post-Modernism Part II

Luther Blissett's recent best-seller, 'Q'

by Stewart Home

Q is an intricate historical novel by four Bolognan authors deploying the name of the inglorious footballer Luther Blissett. Stewart Home, a champion of 'multiple identities' who has also published under this name, detects in Q's cultural bricolage an ascending dialectical movement between rebellious practice and theory.

More than any other art form, even painting at the height of its ‘realist’ phase, the novel is tied to the rise of the bourgeois subject. It is for this very reason that fiction writing has tended to lag behind the other arts, and novels are nearly always ascribed to single authors. Indeed, that past master of bourgeois reaction, George Orwell, made books no longer being written by individuals one of the great horrors of his risible dystopia, 1984. In many arts, and only most obviously music and film, openly acknowledged collaboration is the norm and the ongoing weakness of the novel as a mode of cultural expression can be ascribed at least in part to its one-sided and pseudo-individualistic development. Well established writers tend to find it difficult to collaborate because they insist the stamp of their own style should be left on everything they touch, leading to disagreements and a lack of cohesion when they attempt to work in concert. When one or more collaborating writers find it either difficult or impossible to accept the revision by others of their contributions to a group project, it is each author’s weaknesses rather than their strengths that are multiplied. Innovative writers happily lacking a ready-made cultural reputation are in the fortunate position of being able to take a dispassionate view of those moribund artistic conventions rooted in the notion of style. Thus it comes as no surprise that the most successful recent example of a jointly effected anti-novel should be the work of ‘young unknowns’. The book is called Q and although it is attributed to Luther Blissett, the vigour of its anti-narrative is rooted in the fact that it emerged from the combined imaginations of four young upstarts who just happen to live in Bologna and scribble in their native Italian. The gulf between Q and most of the books currently dominating the bestseller list is the difference between masturbation and sex.

Roof Books

$12.95

96 pp.

The two terms separated by an “or” in the title of Smith’s most recent collection finger out of the lineup of guiltless aesthetic pleasures the axes around which his work to date—collected in two previous books, In Memory of My Theories (1996) and Protective Immediacy (1999)—decidedly revolve, never in fact choosing one over the other but melding them in what must be the most melancholic and vulnerable, and often immediately appealing, writing to come out of the Language poetry tradition so far. Like his two earlier efforts, Music or Honesty is a slim volume that can be read as a single work, and each book can be seen as some continuation of the last. That there is purpose in this overflowing of borders is apparent in the second section of the book, “Autospy Turvy,” which starts with the prose poem “Ted’s Head”—a short parable about the US's latest salesman President based on the Mary Tyler Moore Show that ends: “Now imagine if Ted were Lou, if Ted were the boss. You know how incredibly fucking brainless Ted is, but let’s imagine he understands & is willing to use force. That’s the situation we’re now in as Americans.” (27). The section then segues into a 10-page poem called, again, “Autopsy Turvy,” a more indeterminate but still strikingly satiric excursus on the dark whims of testosterone-driven government (“the sportive hucksters are carping / to the gunshop retirees in the gold dawn”), and ends with the three-page “Dissociadelic,” which, as the neologism suggests, escapes the circuit of rational summarization entirely and usurps the page for the staging of some classic Langpo pyrotechnics: “Look, he’s up in the sky--/ gasping & the roof falls in, etc. / an entire ladder company / holds its bladder America, / It’s not magic if you trust it. / the soft night of weasel balls / beeps” (38) Smith’s more characteristic run-on-but-sonorous style – such as in the section “No Minus,” with its homage of Tom Raworth – is a stand-up theorist’s channeling of both the absurd and the sublime, or perhaps absurd into the sublime, forcing a collapse of both categories in a microtonal melange of lingual rubble. It’s a style one associates with Kevin Davies or John Ashbery's first books after The Tennis Court Oath, in which he's beginning to use a mellifluous line but letting the waves break on the crazy, recalcitrant detail he’s culled from children’s books, dictionaries of old slang and similarly evocative detritus, forcing bizarro yokings of disparate strands of culture: “The mist rises from the bourgeois canopy / to reveal Warburton’s tome Philosophy: The Basics / which is inimitably blurbed by “some / dead motorcyclist’s demystified rock start status” / & it can’t imagine the lord uploading / that hot mass at half-price without checking / with Doctor Said first.” (48) The real game, reading Smith, is the play between determinacy – what the poet “intends” to write and what he “means” – and chance – how the poet grabs onto what swims across his ken and places it, wholesale, into a poem – a collage aesthetic mated with a sort of discovery narrative of the decidedly un-islanded mind. This is ultimately the question of life itself, understood as a daily improvisation dependent on the tools at hand, some of the most useful of which are distraction, unreason, humor, pity and piety, not to mention music and honesty themselves.

DWH: I like to think of myself as a malcontent provider. As someone who works regularly with found text, copping to the “plagiarism” that’s at the heart of all “original” writing doesn’t worry me at all; in fact, I’m beginning to think it’s a necessary strategic position for artists at this particular moment in history. As thinkers like Siva Vaidyanathan and Lawrence Lessig have been arguing strenuously for the last few years, the concept of intellectual property is a relatively recent, regressive invention that has nothing to do with the reasons that copyright was established two hundred years ago, and that it actually reverses copyright’s original function – to provide a short-term monopoly solely to drive innovative thought, not to create perpetual profit. Artists in many disciplines are increasingly moving toward creative processes based on appropriation, sampling, bricolage, citation and hyperlinking, but the multinationals and the entertainment industries are driving legislation in the exact opposite direction by arguing that ideas can and should be owned. Artists and writers who have a large investment in their own “originality” do us all a serious disservice by refusing to recognize and protect the public domain … the very thing that makes ongoing artistic activity possible. So by all means, yes, don’t just “write” (a verb which in many cases bears the superciliousness of the Romantic), build (mal)content. Bring on the hyperlinks, intro paragraphs, pictures, PHP scripts and HTML formatting, especially if they help to demonstrate the mutual indebtedness that all creativity entails. Use Your Allusion.

BKS: Copyright laws may never expire fast enough for internet plagiarizers who want appropriation now, but I haven’t heard anything recently about the Edison company suing Napster, nor did the estate of George Meredith go after David Bowie for stealing “Modern Love.” Unfortunately, for poets it hardly matters—if there were a P2P system for trading poems, we’d love it, and so poetry may be not a rich ground for recruitment in this battle. No one cared about the Vaneigem series until the Times cease-and-desist letter came in (Vaneigem still doesn’t care); it’s the reverse of that Benny Hill routine in which a pervert’s trying to look up a lady’s skirt—once she takes it off and stands there in a bikini, he loses interest. Poets are already in the public domain—we’re floundering there, certainly not unwittingly, but nobody asks permission to steal their turns-of-phrase, their new sentences and rhetorical ticks, or any linguistic innovation. As for creative products geared toward highlighting how indebted creativity is to reworkings of other cultural products—I like them, of course, but didn’t this trend already pass, along with Verfremdung effects in theater— placards, talking to the audience, sweating on them? Kenny’s Day is an exception, but it took him 836 pages to be one. I welcome the challenge of working with language apart from appropriation, I suppose because, on the web, I’m all about appropriation—The Truth Interview, Circulars, etc.—and non-appropriative stuff—programming Flash, “writing” poems—seems fresh again. Ah, the dialectic!

The Figures, 2003

$20

836 pp.

Werner Herzog, the stoic devil that best managed to capture avenging angel Klaus Kinski on film deep in the wilds of the Amazon, once said that a film director is more an athlete than an aesthete -- that stamina is as important as sensibility. Kenneth Goldsmith has made a career out of creating, through masochistically tortuous writing practices, impossibly long, but very simply conceived books that follow through to the bitter end on some writing tick -- either through collecting, for two years, all of the phrases he encountered ending in the sound “r” (No. 111) or by spending an entire Bloomsday recording his every body movement into a tape recorder and transcribing it (Fidget). Book writing is a second career for Goldsmith, as he was a successful RISDY-educated gallery sculpture for several years; a photo project, "Broken New York," was recently featured in a New York Times article. He probably as well known now as the creator and maintainer of the ubu.com website (a huge collection of concrete poetry and sound files), as a provocative, frequently banned disk jockey on New Jersey’ s WFMU, and as a regular reviewer of avant-garde music for the New York Press. Goldsmith’s new book, Day, doesn’t reneg on this promise for extremity -- extremely simple acts repeated to the point of complex insights -- as it is a complete resetting of one day's Times, read linearly across the page (like a scanner), into plain text without missing a sales pitch, a day’s errata note, obituary or punctuation mark. This huge blue tome makes his 610-page No. 111 look like an issue of Reader’s Digest (indeed, any book less completist feels so), creating, of course, a lively air of scepticism (the meat of his art) in the mind of anyone who might chance to “read” it. Of course we must be sceptical -- of course we must be human -- as one was sceptical when Howard Johnsons first started appearing across the American desert and Warhol siphoned millions into his checking account without lifting a brush. But, in fact, Goldmsith is on to something deeper than mere pop bravado, as Day shows that a reader's interests are fed by only a fraction of the available information out there, but one needs this exclusivity, this personal-editing, to gird identity. For a tennis fan, there is a unique pleasure in reading about Andre Agassi's 3rd round loss to Arnauld Clement in the 2000 French Open, just riding the wave of his big comeback, showing he's human and also not yet married to Steffi Graf (a little beyond human) -- and that this "day" occurred before 9/11 adds to the pathos. There's also an obscene -- as in “offstage” -- generosity in this book that treats everyone from the Wall Street brokers (represented by the largest number of pages, pure numbers and business names) to children (in the ads for children's clothes) to, of course, those folks populating the news and entertainment stories (it was a Friday) as equals before the blind deity of digital typesetting and book binding -- an interesting gloss on how history tends to reserve its annals only for the exceptional few (and how it might not have to any longer). Day makes for a giddy anthropology, and if one is to grant that it’s “poetry,” it is the grinning slacker brother to the Chaucer's cross-class ventriloquy in The Canterbury Tales, but one that, in essence, arrives hot off the press every day. It would take weeks to even run your eye over all of this stuff (one generally spends less time “reading the paper”), and the book gives you a sublime sense of how many words are published every second on this planet. Flattening out a pyramid of textual society -- its politics, its banalities, its heroicism -- into a 4th-person narrative like this -- making a newspaper weigh over 5 pounds while in the process engaging in a full frontal act of acidic plagiarism -- is itself a sculptural gesture, but also philosphical one that teases the well-worn point that the value of a text is often in how it’s read than in the words, the sportsman Agassi as unwitting Chaplin-man mascot for this postmodern truism.

[Back by unpopular demand... another installment of my and Darren's backandforth about Circulars. Read below to catch up. I think I get the "content provider of the year" award today -- and this is just the public stuff! I'll be making enemies in my sleep... ;)]

DWH: It’s all to easy too imagine the Marcel Proust blog—Christ, what a nightmare (shades of Monty Python: “Proust in his first post wrote about, wrote about …”). Endless streams of novelistic prose, no matter how incantatory, are *not* what I want to read online. William Gibson, for one, thinks there’s something inimical about blogging to the process of novel-writing. I think that the paragraph-as-“post” is the optimal unit of online composition, and that an optimal online style would be some sort of hybrid of prose poetry and healthy geek cynicism (imagine a Slashdot full of Jeff Derksens). But I think I see your point, that it’s possible for one writer to produce the kind of dialogic multiplicity that could sustain a blog. There is, however, a large difference between “possible” and “likely.” IMO, as less stratospheric talents than the geniuses of high modernism, we stand a better chance of generating strong content collectively. Another model that I find promising is the Haddock Directory -- a site I’ve been reading daily for at least 4 years. Haddock has recently moved to a two-column format: standard blog description-plus-link on the left (maintained by the site’s owner and editor-in-chief, if you will) and entries from the Haddock community blogs, identified by author, on the right. It’s a very neat example of the effective aggregation of data within a particular interest group. And it seems to follow Stein’s dicta “I write for myself and for strangers.”

BKS: I’m still curious about the line “generating strong content”—what do you mean by “content”? My guess is not “writing” as we know it, but some admixture of links, intro paragraphs, pictures, HTML formatting, that creates a dynamic, engaging, and timely space on the screen. “Content” moves from “writing” to the shape one creates by selectively linking to other sites, serving, but also provoking, a “particular interest group.” (I wrote earlier today in a dispute over blogs: “Circulars was a short-term effort (or as short-term as the war) that was a response to what I sensed was, or would be (or hoped to be) a moment of crisis in terms of American self-identification.” Who would have thought, ten years ago, that a group of weblinks and writing could contribute to a crisis in national identity?) Most writers would probably feel demeaned to be referred to as “content managers,” as if all writing were a versioning of some other writing (put it back in your pants, Harold), but, frankly, we’re admitting for a whole lot of plagiarism in this concept of “content.” I think the blog-ring model on haddock.org is strong, since it lets writers tend their gardens, deriving whatever classic satisfactions one gets from writing, and yet contribute unwittingly to a larger collective. I agree: some “types” of writing just work better online—claustrophobic syntax, also non-sequiturs, drives readers back to hunt for hearty prose (though writers like Hitchens seem to be as uncompromisingly belle-lettristic on screen as on paper).

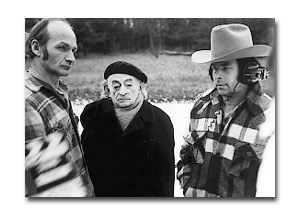

If the name sounds like Woyzeck, it should -- Herzog's original intention was to make a film based on Buchner's play, but he instead made a movie about three very strange Germans who make their way to Wisconsin, buy a trailer home, become (respectively) a prostitute, an acolyte of Mesmer and a car mechanic, and who end up (respectively) in Vancouver, in jail and dead on a ski lift holding a big butterball Turkey. I encourage everyone to see this film, which I saw last night on DVD. The actress, Eva Mattes, is not in the photo below, which features Clayton Szlapinski (an American car mechanic that Herzog met when his truck broke down), Clemens Scheitz and the amazing latter-day miestersanger Bruno S. -- read about him below. I've only been disappointed with Herzog once, in that crappy made for TV thing about mountain climbing that starred Donald Sutherland, but otherwise he is simply too rich to describe, and quite often he is just letting the camera run on things he knows are overwhelmingly strange and beautiful.

The story behind its making is almost as interesting as the film itself. Documentarian Errol Morris wanted to make a film about the town of Plainfield, Wisconsin, from which eight serial murderers came, including the infamous Ed Gein, inspiration for Psycho and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Morris discovered that Gein dug up all the graves in a circle around that of his mother, and he and his friend Herzog decided that the only way to find out if he dug up his mother's grave too was to dig it up themselves. Morris never showed up for their meeting, and Herzog's car broke down in Plainfield. His experiences, and many of the people he met there, are here in this film. That story is seamlessly blended into the life story of Bruno S., the star. Bruno was abused by his drug-addict mother and abandoned when he was three. He spent the next 23 years of his life in various mental hospitals and prisons. Herzog discovered him as a gifted street musician and cast him in his The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, whose story also echoed Bruno's life. (Read rest at link above.)

Gary's posted a short rejoinder on his site... he asked in his backchannel email to me if I thought his rejoinder was too mean, but in fact, I was being mean -- I guess these are the day of getting, and then riding, the goat.

Well, Gary's come out swinging on his weblog, and it's not like I have nothing better to do today but I frankly think he was swinging low... here's my riposte. (None of us have time for more headaches, so hopefully this will fade quick.)

Hey Gary,

Well, this gets MY goat -- I'd be happy to see this go away, but you really go pretty low here -- I'll apologize in advance for taking you up on all your points, and hope this doesn't hurt your feelings. Maybe you could post my response on your weblog?

> DWH's comments above, unlike Swift's brilliant, exhaustive

> excoriation, lack any measurable sense of experience with the medium

> he's dismissing.

Darren's written over 4 books on the subject, and is the creator of both alienated.net (which you should know) and Free as in Speech and Beer, which is a spin-off of his book of that title -- so, if that's a way of "measuring" a "sense of experience," then let's use it.

If by "medium" you mean "personal weblog," then you do not medium as he clearly means it in his paragraph, which is the medium of the internet. Consequently, if you are comparing Darren's blog prose-style to Swifts, you might as well compare Silliman's to Coleridge's, or your own to Mark Twain's -- and then you are right in there with Darren, chanting "anemia," since neither you, nor Silliman (nor I) write so well. Nice tautology.

> I've already argued here for the value of personal weblogs--has Sei

> Shonagon's unedited, "formless" Pillow Book grown "thin" over time?

"Thin over time" -- I think we are talking about two different times here, that of history and that of, say, the daily news. I'm sure there is a blog out there that, collected in its entirety, might be worth reading several years from now, but that's not quite what we are talking about, is it? And because one person succeeds in a "genre" does not free the genre itself for all criticisms. Certainly the historical and romance novel has had its many brilliant successes, but for the most part they are not done well for reasons endemic to the culture that often produces them, that of the cheap paperback novel. So does that mean we don't try to imagine what a good historical novel might be like?

> mostly gender-centric assumptions

This is truly playing to the crowd? Darren's a man, eghad! (Wow, it really gets worse below... Gary, this is disappointing.)

> Let's look at two key words: "over time." Note that, for instance,

> Circulars (which DWH, as well as BKS, had a significant hand in), has

> slowed down significantly in since the invasion in Iraq--it's still

> being updated, but not at all with the collective excitement the site

> enjoyed in the first three or four months of its existence. "Over

> time," the content (literally the content) of Circulars has, in fact,

> thinned--to a proportionally greater degree than, say, that of

> personal weblogs such as Nick Piombino's Fait Accompli or Eileen

> Tabios's CorpsePoetics (formerly WinePoetics). This need not be the

> fate of a politically oriented, multi-authored web publication: take a

> look, for instance, at counterpunch.org.

Counterpunch is a muckraking newsletter that has a paid staff. Circulars was a short-term effort (or as short-term as the war) that was a response to what I sensed was, or would be (or hoped to be) a moment of crisis in terms of American self-identification. But like sports, crises has its seasons, and as you know having seen Circulars, it was a site with a mandate to collect the "disparate activity of poets" out there -- if there is no such activity, then certainly I can't collect it. Nor can I write it -- Coburn and St. Clair are professional journalists who make it there business to churn out prose -- it's what they've trained themselves to do, whereas I've trained myself in something quite different in terms of writing. They have a network of journalists (there is, after all, much more writing on political issues than there is about off-the-cuff journalism about poetry). Anyway, the comparison is specious: Counterpunch is not a weblog, it has a budget, a press office, etc. You know that. And as you know, I announced the death of Circulars weeks ago -- it didn't mysteriously trail away -- the point being that, next time, it could be done better, starting afresh. The paragraph that Nada is commenting on is in fact from an "exchange on Circulars" -- we're thinking of how to do it better. Anything wrong with that?

> DWH uses the modifier "anemic" to describe what he sees as an

> inevitability: the diminishing returns of personal weblogs. Without

> getting into Sontag's "Illness as Metaphor,"

(Why not? I can't imagine anything in it would be as low as what you write below...)

> there's something gender-specific about that particular word and the

> images it may conjur up: It is, after all, women who most often suffer

> from anemia--Nada, for instance, whose strong reaction to DWH's post

> you can read in the "comments" section following DHS's original

> post--has had at least two life-threatening instances of the

> affliction. Would, I wonder, DWH use "diabetic" in a similar way?

> Doubtful.

This is absurd. Plenty of men have anemia (from hemorrhoids, as it turns out, but also just plain old disease). And so did my mother (not from hemorrhoids), for years, and I'm not offended. And she's Korean, could have been a lack of iron in her Korean diet -- did Darren know that? This is low and ridiculous, frankly.

> Why not? Let's be frank: unconsciously, DWH probably would *not* use

> an illness as metaphor that he associated with someone he knows and

> respects. Anemia is a "safe" illness to use as metaphor--unlike AIDS, it's not un-PC to use it this way; unlike diabetes, it's probably not something any of his male writer friends actually has. It is, in fact, something *women* (and old people) have.

You mean, because Steve McCaffery and I are diabetic, he held back from calling webblogs "hypoglycemic"? This is a unique bit of reasoning. And what do you, or anyone else, know about Darren's "unconscious"? What are *you* unconsciously writing about then?

Andrea Brady recently told me that she was "hemmoraging money" in New York -- did I take offense because old people hemmorage more than young? Because hemmoraging leads to anemia? Would you?

> The public journal has, since the Heian period when Sei Shonagon

> authored hers, been associated with "women's writing." Blogger's

> precursor, Diaryland, was decidedly gendered (in look and attitude)

> *female*--assumption no doubt being that the personal journal is

> something chix do.

Most of the bloggers on my blogroll are male because most of them *are* male -- one of them has a blog called "The Jism" -- and I cringe every time I see that name there. Do you? And this business about the public journal going back to the Heian period -- well, what are the great public journals of the last 500 years? Just because it's from a different culture (an "Oriental" culture, I might add), and a different time, does this exotic "otherness" give it authority? Of course, I won't press this point.

> What, one wonders, does DWH consider to be "content"? Anyone who has

> read his wonderful book, Tapeworm Foundry, is probably going to be in

> the dark. (The work decidedly comes down on the Form side of the

> Form/Content divide. It's a oulipoianesque formal game--a good

> one--but a game, nonetheless.)

Sorry Gary, but I have to point out that there's nothing Oulipian about Darren's book -- it's just a string of ideas for poems and performance art projects, hardly formal -- it's a mess, it's more like Cage, loose but all "written," and full of "content" -- you make it sound like Barrett Watten's early work here. Just because it's not confessional content does not mean it's not content. Darren's book can be seen at www.ubu.com/ubu.

> Certainly, if we are to take what DWH says in the Circulars exchange

> at face value, he does not consider one's personal thoughts, opinions

> and emotions to be content--or they are, anyway, *thin* content.

Utterly beside the point. First of all, Nada is responding to an expression of Darren's "personal thoughts," and certainly to his "opinion" -- her complaint, in fact, was that it was "opinionated" (ironic for her of course; she, as do you, as do I, obviously believe that having "opinions" and knowing what they are is important in terms of self-identity). And just because someone splashes on a page "I feel like shit today" does not mean that they are expressing emotions in a way that makes for worthwhile reading -- otherwise, writing would be very easy, and we'd all have best sellers.

Why is it so crazy to think that one has to spend time in writing, and that writing "emotions" is practically the hardest thing to do? I'm amazed at how easy everyone thinks writing is!

(And frankly, if you thought that blogs were at their best when they were in the process of writing "emotions", then why was your St. Mark's blog issue entirely concerned with literary criticism -- didn't have any space for emotions there?)

> Dig the tone of the language he uses: Very Professor Tweed Condescends

> in order to Set the Freshman Girl Straight: "There's nothing *wrong*

> with personal weblogs ..."

You make it sound like he is responding to Nada when in fact Nada is responding to a semi-private correspondence that Darren and I are having and that I'm posting to my blog. Nice camera trick -- "fixed in the edit" -- but it's wrong.

> which have seen Everything! Everything!

Maybe you should read one of the many books he's written on the subject (none released in the US, unfortunately, but in the "elsewhere" of Canada, which I guess isn't far away enough). Why go over the top when you lack basic facts (and, of course, Nada thought Darren wrote "Eunoia").

> before suggesting that one way of addressing anemia is to do "more

> collective writing"--in other words, girls, you really *are*

> incomplete without your (male) Other. Oh, and, in Perfect Professor

> fashion,

Darren's a professor? I've seen you wear more tweed. (You are really beating a rather dead-non-horse here with the gender thing. This is, I dare say, a great example of how an argument can go "anemic" over time.)

> he reminds Freshman & Lapsed Freshman Chix Everywhere: "The problem is

> partly a need for education."

Yes, the education word kind of bothered me here, too, but I think he meant "self-education" -- as in what I did, teach myself a few things. But so he's suggesting that, well, now that we're in the web world, why not take it the next step instead of being bystanders? The internet is there for the taking, why trivialize its great potentialities.

> Uh huh. Of course it is. That's *always* the problem. Because, you

> see, without it, that grand and beautufully Male Thing: Ed(it) YOU

> Cation -- you see, without THAT, people can fall into a dangerous

> space where they begin to think their own thoughts, imagine their own

> futures, and create their own works of art.

Yes, male = edit. Or, male = education. Or whatever, not sure what the point is -- that the women in Afghanistan are not happy about going to school because it's a male thing to do? I'm sure I could list a thousand female poets who edit more than, say, Ron Silliman. Who, by the way, is the most prolific blogger out there. If one really cared for one's own thoughts, one would take the time to write them out very carefully. Original thoughts are, after all, hard to come by.

> DWH's message: Join the Boy's Club. Become Part of the New Old Boy's

> Network. (Note that these multi-authored blogs tend to be male-run,

> and largely male populated.)

Dude, as I said, drop the "multi-authored" from the above and you are talking about blog culture in general. And what multi-authored blogs are you talking about -- you sound like a professor here! You must know something I don't, because you seem to have the entire culture under your thumb! Was there not about a %75 to %25 male to female ratio at the commix convention the other day? Feel guilty? Not me (title of an Eileen Myles book concerned with independent thinking).

(I think it's useful to believe that some people know more about something than I do, like I know that you know more about commix than I do -- doesn't mean I'm a sycophant. I think that equation is harmful.)

> So, where does this language and attitude of DWH come from, and where

> will it lead? Simple: If one *really* wants others to join them, to

> work with them, on some possibly politically relevant or even

> potentially utopic site--it's *crucial* to be arrogant andor

> dismissive andor sexist andor ...

right. Either way, the men win again.

I think the idea is basically that sets of 2 panel cartoon are reconfigured based on the phrase you enter? Or maybe it's entirely random? The basic style is indebted to the little proselytizing pamphlets of Jack Chick.

![frok4[1].png](http://www.arras.net/weblog/frok4[1].png)

![frok13[1].png](http://www.arras.net/weblog/frok13[1].png)

![frok20[1].png](http://www.arras.net/weblog/frok20[1].png)

![frok5[1].png](http://www.arras.net/weblog/frok5[1].png)

I’m not sure that it’s necessary for a blog to be multi-authored; what it really needs is a mandate, and it’s possible that, were the mandate simply to produce rich, incantatory prose—imagine the Marcel Proust blog—a highly disciplined approach could work. Steve Perry’s Bushwarsblog, for example, succeeds quite well on this level (not the Proustian but the muckraker), as does Tom Mantrullo’s Swiftian Commonplaces. Both of them have “political” agendas, but they are also well-written and thoughtful for what are in effect news publications without an editor. It helps that these two are journalists and conceptualize their blogs as a distinct form of news writing alternative to the mainstream—the individual voice is sharpened by an informed sense of the social arena in which it will resonate (in which the message will ultimately become dulled). Just today, Tom posted a link to the Times story on corporate blogging—yecch—and has coined this aphorism, a detournement from Foucault though sounding somewhat Captain Kirkish to me, to describe his project: “To blog is to undertake to blog something different from what one blogged before.” A version of “make it new” but with the formal precedent being the blog itself—a vow not to let individual “multi-authoring” become equal to corporate mono-glut. Perhaps the model blog is that which responds to the formal issues of other blogs as if they were social issues (i.e. beyond one’s “community”), hence transforming the techne of the writer into a consideration of hypertextual “craft.”

[The New York Times had a story about the "corporate blog" a few days back -- I have yet to read it myself, but here is the beginning of Tom Mantrullo's little rant about it, referring to another blogger's call for (corporate)self-immolation.]

from IMproPRieTies:

Jeneane sees corporate blog, slays self:

Who will join me in leaping to a firey death after reading The NY Times article on "The Corporate Blog"?

To blog is to undertake to blog something different from what one blogged before.

Christopher Hitchens on the nature of generational identity -- which I myself always found rather silly, as if every poet born in 1926 had something to do with the others -- in his usual succinct terms. What does one do to become part of one's time, I guess is the question.

So let me ask you, how do you think you were affected by the sixties?

I have no choice but to put myself in a political generation. But I'm glad you say the sixties because I've always thought that of all the kinds of human solidarity, the generational is the lowest. (I wish I could find out the name of the person who said that.) Because what do you have to do except have an accident of birth? I mean, to be a sixties person, all you have to do is to be born in a certain year, like select wine, except not as good. To be a '68-er, however, a "soixante-huitard" -- we even have a French term for it now -- you have to have been someone who in some sense felt or saw the '68 crises coming, and was, in some sense, ready for it, or, if not that, was totally swept up in it, realized that here was a crux moment, a hinge year. I'm lucky in that I made my decision that I thought it was going to be key in '67, the year I went to Oxford actually, and joined a small Trotskyesque/Luxembourgist organization, which in the next year quadrupled ... no, much more than quadrupled its membership.

Conversation with Christopher Hitchens, p. 2 of 5

Despite the minor note of unpleasantness left on TOB (This Old Blog) this morning by Nada -- to which John Donne has already fashioned a response -- Gary has posted a detailed, fun bit about our trip to the comic books convention here in New York yesterday afternoon. I wasn't quite as envious of the crowds as he suggests, however, it's just that the only time I've seen roomfuls of people crowding around tables full of poetry books was during the "poetry talks" event that Rob Fitterman put together in NY in 1995, at which there was only a fraction of who was there yesterday. I'm not sure I'd want poets to hawk their wares in quite the way these artists were yesterday -- "This is the guaranteed funniest comic you've ever read... If you do not laugh out loud when you read this, you can email me and I'll give you your money back" -- this guy was charming, but serious. His comic book was in fact funny, but I didn't buy it. I did buy for Rachel a cute little stapled book called Astrophysics: Big Questions No. Three, which featured a bunch of sparrows and an unexploded bomb that had been dropped on their nest out of a B1 or something. When the sparrow goes over to the wise owl "Alma" to ask what this large humming "egg" was doing in their yard, Alma (who didn't, it appears, speak sparrow) ate him. The bomb, meanwhile, didn't go off. Wisdom for the ages. The artist, Anders Nilson of Chicago, autographed it for Rachel with a nice drawing of the bottom of a car -- I smacked him for trying to pick up my girlfriend, and ran away.

I've only made about 3 successful translations of anything in my life, one from Rimbaud (Seven Year Old Poets, in Angry Penguins), one from Virgil, and one from Jules Laforgue, the 19th French poet who died at 27 and was influential on Pound and Eliot. Here's the French, followed by my "version" -- more in the "love" theme mentioned earlier, but obviously of a different tenor.

Que loin l'âme type

Qui m'a dit adieu

Parce que mes yeux

Manquaient de principes !

Elle, en ce moment,

Elle, si pain tendre,

Oh ! peut-être engendre

Quelque garnement.

Car on l'a unie

Avec un monsieur,

Ce qu'il y a de mieux,

Mais pauvre en génie.

Oh, that model soul

bade me her adieu

because my eyes… too?

lacked principle.

She, such tender bread

(now a Wonder loaf)

…typical! gives birth

to one more brat.

For, married, she is

always with a guy

who is a nice guy,

hence his genius.

[The continuation of my dialogue with Darren Wershler-Henry... see below for the beginning.]

DWH: I’m not suggesting that blogs and newsforums should be about the abrogation of editorial control – far from it. It’s always necessary to do a certain amount of moderation and housecleaning, which, as you well know, takes assloads of time. During its peak, I was spending at least 2 or 3 hours a day working on Circulars, and I’m sure you put in even more time than that, even with the help of the other industrious people who were writing for the site. Which takes me back to the value of the coalition model: a decent weblog NEEDS multiple authors to work even in the short term. The classic example of a successful weblog is Boing Boing, a geek news site that evolved from a magazine and accompanying forum on the WELL in the late 80s/early 90s. Mark Frauenfelder, the original editor, has worked with many excellent people over the years, but the current group (including Canadian SF writer/ Electronic Frontier Foundation activist Cory Doctorow, writer/video director David Pescovitz and media writer/conference manager Xeni Jardin) presents a combination of individual talent and a shared vision. There’s nothing *wrong* with personal weblogs, but, like reality TV, they get awfully thin over time. Even when the current search technologies adapt to spider the extra text that blogging has created, the problem of anemic content isn’t going to go away unless we start doing more collective writing online. The problem is partly a need for education; most writers are still in the process of learning how to use the web to best advantage.

Here's a rough draft for a poem... actually, it's one poem in a sequence, all of which follow a certain stanza pattern that I'll let you figure out (keep your eye on the semi-colons). This is, again, a rough draft, basically a first draft -- it gets quite clogged at the end, and the opening line is kind of a clinker, and I'm distrustful of the rhetorical conceit in the middle, etc. etc. It's from the same file the shory from below is taken. Some of the lines might carry over to the next in your browser... sorry. By the way, the new Radiohead album is great.

Not assured of the hedonist’s rapture, or the safety of guiding ropes;

he has a normal name otherwise, nothing to suggest television,

drinks too much perhaps, is over-studied for literary conflagration;

the list, otherwise, grew blurry, once including: “syncresis,” “allotropes,”

“Marxism” (also, “Leninism,” “Stalinism”) and “individualist”

for contrast, also “humanism,” “realism” (vs. “social realism”), madly “Darwinist”;

in Vancouver, these are just the names of punk rock bands, all

pant-legs to rumbles, prismatic (where stateside they would be “dualists”),

paragrammatic, encoding the revolution by frobbing syntactical

dials, forgetting, before the moderns, we claimed Bliss Carmen for “ourselves”;

Williams would have loved him, as likely Pound, Zukofsky, and Marianne

Moore, his neighbor, but for us he’s Ashbery-meets-Gibson (William, not Mel),

Philip K. Dick channeling Spicerian Lenny Bruce through old coffee radio of

insomniac Chomskyite nites, perfectionist, though perhaps no Gautier (Theophile)

in form—a world without embellishment, sans vorpal swords, only contacts.

The shortest, most sentimental thing I've ever written, which I just discovered in an old word file...

And we reach

for the last

thing available

and what is

available is love.

That could almost be on Nick Piombino's blog... well, I'll resist the urge to delete it because I've already deleted it from the word file whence it sprang... sprang rhythm, get it?... not to mention a certain affection for the double "is"s in the last two lines, which force a reread -- c'mon, be honest, you read it twice, right? Just to get a better sense of the cadence? Gotcha.

Just chanced upon a nice article on Ian Hamilton Finlay in the Guardian UK... now, is he a poet of "quietude"?

Guardian Unlimited | Arts features | Profile: Ian Hamilton Finlay

[I received this email a few days back from Rachel Blau Duplessis in response to my Flash poem -- which she hasn't yet seen, I gather -- called "The Dreamlife of Letters," which was based, in a sort of twisted, algorithmically-enriched (or impoverished, depending on your pov), on her contribution to "A Poetics Colloquium: Body/Sex/Writing," forum enacted entirely through email on the Buffalo Poetics List in 2000. The email is also addressed to Dee Morris, who had presented a paper on Dreamlife at a conference somewhere (don't know the details on this). Rachel was spurred to write this by reading the dialogue, called "potentially suitable for running in a loop," that Darren Wershler-Henry and I had for a Cyberpoetry issue of Open Letter some years back and which appears now in Fashionable Noise. Anyway, that's the background. She gave me permission to post it here. (I've found my own original response to the colloquium online as well, which contains the original "dreamlife" poem.)]

email from Italy on 10 June 2003 to Dee Morris and Brian Kim Stefans. Hi both, one of you my dear friend, and the other an interesting acquaintance. The one will (I hope) forgive my odd tone in writing a double email,; the other will (I hope) forgive the bolt-from-the-blue aspect of this. I just received Brian’s book from Atelos, the day we left for Italy, and (while I left it at home) I had a chance to glance at the first essay and was struck by how it began with that orchestrated exchange that Dodie proposed a few years ago—in experienced time, eons ago. That is, Brian, you are talking about me, or being queried about that intersection of our work. So I just looked at Dream Life (again,) today, though, NOT in its flash form. I’m sorry about that, but I didn’t want to overload my simple hookup here (one laptop, thru an Italian server etc). That this unwillingness to have my screen saver taken over by your text (! scary warning!) might express a smidgen of resistance to things not lying flat on the page—well, so be it. That this is a belated response should surprise no one who knows me—it does not mean wound, hurt, insult, rage, etc—I am just slow. Brian—the wittiness of your work "The Dream Life of Letters" is patent. I think you did a remarkable thing with the terms I had set up. The alphabet and the mini-poems are charming and clarifying, actually. And gaffaw-laden. Although I don’t know whether my text was "too loaded," it does cover the territory in 2 ways, and I appreciate the challenge you met. It must have been hard to leverage anything into mine. Looking at your work today, I am intrigued by the words that repeat: dream, gender, in and no. No is actually a very important word for me, and the "N" of No actually begins Drafts. I’m writing because I want to tell you what I did, since you may not exactly have gotten it (or did you?) and tell Dee too, because now she seems to have written about this intersection of materials, but esp about Brian’s work as web poetry. (So I also wanted at long last to ask Dee to email me her paper by attachment if she could.) I frankly do not remember totally what Dodie asked us to do, but it was about sexuality and the polymorphous. I have read some Kristeva and Cixous and Irigaray, and Chodorow, and am intrigued (helped along by this theorizing) about oedipality and pre-oedipality in its ideas about how sexuality and gender are constructed. It seemed to me a simple extrapolation from this theory that people might not be gendered in their dream life, at least not in the same way they are in their day life, because oedipality is normativity, but preoedipality leaks thru in all sorts of ways including in the unconscious being explored in dream. This means we spend a lot of our lives not gendered in the way we more-or-less are, and not enacting the sexualities we expect of ourselves—but this part of our lives is asleep. I wrote a statement about this idea. Then I made a homophonic translation of the statement, as a staged example of preoedipal "babble" or the voice of the "chora." Two format issues then took over. One I intended, but the other just simply occurred, and will occur in any random formatted site that is run on its own default. The intended one: I placed the homophonic translated babble FIRST, before the sentences I wrote. I did not want the rational language to take precedence. The other—I worked by prose, but translated it line by line as the prose came up on my computer. One set of statements was simply set on top of the other, and in the original format, you could really see homophonic translation and then text, which gave a good idea of the pivotal balancing of analytic statement and broken-wild language. However, other formats will run the babble and the statement together in ways that differed from the original presentation. Brian—cutting thru this with alphabetization had a lot of flair. But it is also true that words without syntax, and playing with repetition necessarily changes the social and cultural bearing of my message, insofar as it was a message, or sort of a thought-provoker. This is the suggestion made by your interlocutor in the Atelos book: that your text has the effect of "losing" the feminism. You didn’t really answer him—and the issue might be unanswerable. You don’t, at any rate, seem to reposition the feminism. HOWEVER, there is a sense of aesthetic detournement, hard generationally for me, but something to face. That is, same story—**I** was supposed to be doing the "detourn-ing"! And you ended up doing it. Or perhaps we can share—we both did. But I think, nonetheless, that the exchange is great, even if your alphabetizatioon necessarily is an organization only of the babble part of my piece. (And the letters are in flight and play on the flash program—right?) So it’s interesting that you did The Dream Life of Letters, while I did The Dream Life of Genders. The relationship of any feminism to the avant-garde has been in play ever since Loy wrote "Feminist Manifesto" in 1914—or probably before. I think we (Brian and I) are re-staging this push and pull. any comment? thanks for listening. warmly, Rachel

Digital Art

Christiane Paul

$14.95

0—500—20367—9

224 pp.

Thames & Hudson

Probably no birth of a genre has been celebrated as much as that of “digital art”—in some quarters known as “new media art” and others the “information arts”—and Paul does an impressive job where many of her bigger-budgeted, theoretically-enthralled predecessors have failed, compressing the activity of a huge field in which there are no obvious heroes, no single aesthetic line, into a readable pocket-sized book.

She is especially deft at laying the groundwork for such diverse practices as "telepresence" (the transferring of an artist’s or user’s activities over telephone to other parts of the world) to “browser art” (the creation of alternative browsers to navigate and present web data) and “hacktevism”—political art, often aimed at corporations, that is also a guerilla warfare enacted through hacking, viruses, and other forms of maverick programming.

Paul adequately explains why certain analog arts, such as photography, sculpture and even literature have been so impacted by digital technology as to spawn entirely different genres.

For those who have been following this fast developing field—it grew exponentially in the nineties, though had been thriving in video and sound art much earlier—everybody you’d expect to see is here: from the Barcelona-based web art team jodi (Joan Hemskeerk and Dirk Paesmans) to new York's Asymptote architectural team (founded by Hani Rashid), from Robert Lazzarini’s 3D anamorphic skulls to Eduardo Kac’s weird experiments with animal genetics (he once bred a glow-in-the-dark rabbit).

In fact, there are so much art covered that Paul is often forced to contain her discussion of an artist’s (or team’s) entire body to a few sentences; occasionally, she is able to grant a paragraph, but in many cases, the most information is found in the capacious captions that accompany the many illustrations (many of the artists, luckily, are under 35, several under 30, and so have only a few major pieces under their belts).

If there is a flaw to this book, it is in the uneventful prose style and recourse to abstract postmodernisms to explain the meanings of an artwork. A sequence called The Bone Grass Boy by Ken Gonzales-Day “challenges differences and boundaries between cultures, race, and class, as well as those between the photographic and digital media, both of which raise questions about their relationship to representation” (37)—not the kind of thing to make you jump and say “ah.”

But in general, Paul doesn’t get lost in this language (which is really endemic to the culture, and so her parroting of these phrases doubles as a sort of reportage) and one learns to appreciate the brevity of her style, along with the lack of evaluative affect, as the image of a burgeoning new art culture—independent of the gallery system, infused with the spirit of innovation and even a jingostic attitude toward the new media—takes focus.

[Ok, call me narcissistic... but I was checking to see if Barnes and Noble is carrying my new book and noticed the following information when going to the pages for my past books -- Billy Collins, Homer and I share some fans!]

Angry Penguins

Brian Kim Stefans

Our Price: $9.00

Readers' Advantage Price: $8.55

People who bought this book also bought:

Nine Horses: Poems Billy Collins

The Rose That Grew from Concrete Tupac Shakur, Karolyn Ali (Editor), Foreword by Nikki Giovanni

The Odyssey Homer, George Herbert Palmer (Translator)

Inferno Dante Alighieri, Archibald T. MacAllister (Introduction)

Paradise Lost John Milton, John Leonard

Gulf

Brian Kim Stefans

Paperback, April 2000

Our Price: $7.00

Readers' Advantage Price: $6.65

People who bought this book also bought:

A Patriot's Handbook: Poems, Stories, and Speeches Celebrating the Land We Love Selected by Caroline Kennedy

Nine Horses: Poems Billy Collins

Prophet Kahlil Gibran

The Book of Counted Sorrows Dean Koontz

The Odyssey Homer, George Herbert Palmer (Translator)

[I then checked to see if a few of my friends were quite as lucky as I was, and discovered that Miles Champion, Christian Bök and I share some fans -- do you think there is one person out there buying our books and Billy Collins? Then why don't I appear on Miles' list, and vice versa? Or is it four separate people on different instances buying a Billy Collins book and one of ours? Hint: Billy Collins doesn't appear on lists of books bought for those poets who actually sold copies through B & N, such as the esteemed Jennifery Moxley!]

Three Bell Zero

Miles Champion

Paperback, May 2000

Our Price: $10.95

Readers' Advantage Price: $10.40

People who bought this book also bought:

A Patriot's Handbook: Poems, Stories, and Speeches Celebrating the Land We Love Selected by Caroline Kennedy

Nine Horses: Poems Billy Collins

Prophet Kahlil Gibran

The Book of Counted Sorrows Dean Koontz

The Odyssey Homer, George Herbert Palmer (Translator)

Eunoia

Christian Bok

Our Price: $16.95

Readers' Advantage Price: $16.10

People who bought this book also bought:

Dictee Theresa Hak Cha

Nine Horses: Poems Billy Collins

Foolish/Unfoolish: Reflections on Love Ashanti

Sailing Alone around the Room: New and Selected Poems Billy Collins

Leaves of Grass Walt Whitman

The Sense RecordJennifer Moxley

Paperback, May 2002

Our Price: $12.50

Readers' Advantage Price: $11.88

People who bought this book also bought:

Tender Buttons Gertrude Stein

Touch of Topaz Pat A. Larson

S*Perm**K*T Harryette Mullen

The Haiku Anthology Cor Van Den Heuvel

[Continuation of last story, paragraph 5. I'm pretty sure we're going to move to two paragraphs each, if that means anything to you... it all seems so sketchy. Dark, dark.]

BKS: I haven’t been too bothered with those aspects of Silliman’s Blog for the mere fact that it would double his time having to respond to the comments, many of which could be vicious flames. I’ve deleted some of the comments on Circulars, in one case because the poster was making scandalous allegations (drugs, child molestation) about the head of an advertising agency, and another because the poster, in American fatwa-esque fashion, deemed that I should have a rocket shoved up my ass. Of course, your point is well taken—Silliman’s Blog could use some real-time play-by-play; I’m sure a diagnostic essay is forthcoming. I did set Circulars up with the intention of there being subsets of discussion on the site, separate groups of people who would engage with each other over some time—“committees” of sorts, with their own story threads. This happened for a brief period—there was a lot of heat generated by one of Senator Byrd’s speeches against the war, and there was a discussion about Barrett Watten’s “War = Language.” I was prepared to develop new sections of the site if anyone so requested, though I confess to being dictatorial about the initial set-up, basically because I know more about the web than most poets and I hate bureaucracy. I was hoping that some of the more frequent poet bloggers who were writing political material would send their more developed writing to Circulars, but most posted to their own blogs without telling me, which was understandable.

[I've been asked to write an essay on Circulars for a volume on internet culture. The essay is going to be in three parts: the first, a basic description of what the site was about in its heyday, the second speculations on the "poetics" of the site -- basically, how its forms of "meaning" operated in ways different from other forms of protest/activist sites, and the third composed of an exchange between Darren Wershler-Henry -- who was one of the site most prolific contributors and who has written several books about in internet communities and alternative business models -- and myself. We are simply sending each other 250 word paragraphs -- I figure the restraint would keep it from getting out of hand and force us to do odd things with the grammar to get our points across. It also mimics the form of the "data packet" that underlies all forms of electronic communication. Anyway, I don't know where the dialogue is going -- we're up to 5 paragraphs, but I only have 4 at this computer. It's a bit awkward so far -- we're trying to keep at it fast but ugly -- so here goes...]

BKS: I’ve come up with an awkward, unsettling title for this essay: “Circulars as Anti-Poem.” I’m sure cries will be raised: So you are making a poem out of a war? The invasion was only interesting as content for an esoteric foray into some elitist, inaccessible cultural phenomenon called an “anti-poem”? (There is, in fact, a lineage to the term “anti-poem” but I don’t think it’s important for this essay.) This legitimate objection is to be expected, and I have no reply except the obvious: that a website is a cultural construct, shaped by its editors and contributors, and more specifically, Circulars had a “poetics” implicit in its multi-authored-ness, its admixture of text and image, its being a product of a small branch of the international poetry community, etc. Of course, the title also suggests that this website has some relationship to a “poem,” but perhaps as a non-site of poetry – as it is a non-site for war, even a non-site for activism itself, where real-world effects don’t occur. But my point for now is that the fragmentary artifacts of a politicized investigation into culture – Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks for example -- has an implicit “poetics” to it, but standing opposite to what we normally call a “poem.” This suggests roles that poets can play in the world quite divorced from merely writing poetry (or even prose, though it was the idea that poets could contribute prose to the anti-war cause – as speech writers or journalists, perhaps – that initially inspired the site.

DWH: Hey Brian: what are you using to count words? MS Word says the previous paragraph has 254 words; BBEdit says 259 (me, I'm sticking to BBEdit). Poets -- particularly poets interested in working with computers -- should be all about such subtleties. Not that we should champion a mechanically aided will to pinpoint precision (a military fiction whose epitome is the imagery from the cameras in the noses of US cruise missiles dropped on Iraq during the first Gulf War), but rather, the opposite -- that we should be able to locate the cracks and seams in the spectacle ... the instances where the rhetoric of military precision breaks down. As such, here's a complication for you: why "anti-poem" instead of simply "poetics"? Charles Bernstein's cribbing ("Poetics is the continuation of poetry by other means") of Von Clausewitz's aphorism ("War is the continuation of politics by other means") never seemed as appropriate to me as it did during the period when Circulars was most active. The invocation of Smithson's site/non-site dialectic is also apposite, but only in the most cynical sense. Is the US bombing of Iraq and Afghanistan the equivalent of a country-wide exercise in land art? In any event, the relationship is no longer dialectical but dialogic; the proliferation of weblogs ("war blogs") during the Iraq War created something more arborescent -- a structure with one end anchored in the world of atoms, linked to a network of digital nonsites.

BKS: I hesitate to tease out the “non-site” analogy -- the site itself is too variable: for me, I was thinking of Circulars as being the non-site of activism, not just a corollary to the sweat and presence of people “on the streets” but a vision of a possible culture in which these activities (otherwise abandoned to television) can exist, not to mention reflect and nourish culturally. That is, are our language and tropes going to change because of the upsurge in activity occurring around us – in the form of poster art, detourned “fake” sites, maverick blogging? I admit that some of what we’ve linked to is nothing more than glorified bathroom humor, but nonetheless if the context creates the content for this type of work as a form of dissent, I think that should be discussed, even celebrated. I haven’t read too much about this yet. Thinking of Circulars as the “non-site” of the bombing itself is both depressing and provocative: it’s no secret that one of the phenomena of this war was not the unexpected visibility of CNN, but Salam Pax’s Dear Raed blog, written by a gay man from the heart of Baghdad (even now he is remaining anonymous because of his sexuality). I could see Circulars as a “poetics” but I prefer to think it as an action with a poetics, my own tendency being to think of poetry as the war side of the Clauswitz equation, simply because poetics seems closer to diplomacy than a poem.

DWH: The variability and heteroegeneity of the site, was, I think, partly due to the infrastructural and technological decisions that you made when putting the site together, because those decisions mesh well with the notion of coalition politics (I’m thinking of Donna Haraway’s formulation here). The presence of a number of posting contributors with varied interests, the ability of readers to post comments, the existence of an RSS (Rich Site Summary) feed which allowed anyone running a wide variety of web software packages to syndicate the headlines, a searchable archive, a regular email bulletin – these are crucial elements in any attempt to concentrate attention on the web. Too seldom do writers (even those avowedly interested in collaboration and coalition politics) take the effect of the technologies that they’re using into account, but they make an enormous difference to the final product. Compare Circulars to Ron Silliman’s Blog: on the one hand, you have an deliberately short-term project with a explicit focus, built around a coalition of writers on a technological and political platform that assumes and enables dialogue and dissent from the outset; on the other hand, an obdurate monolith that presents no immediate and obvious means of response, organized around a proper name. Sure, the sites have different goals, but Silliman’s site interests me because it seems to eschew all of the tools that would allow any writer to utilize the unique aspects of the web as an environment for writing. And sadly, it’s typical of many of the writers’ blogs that exist.

Craig Dworkin's created a page of 30 music reviews of entirely silent pieces (the first review being, of course, of Cage's 4'33"). And they're not all favorable!

Just discovered an interesting group blog concerning digital textuality and literature, run by Michael Mateas, Nick Montfort, Stuart Moulthrop, Andrew Stern, Noah Wardrip-Fruin -- I've met most of these folks, Noah having participated in the Mini Digi Po event here in New York, and Nick and Stuart hosting their own events which I've attended.

Some good, detailed and cogent discussion for those interested in the field, though as usual I have reservations about a horse-before-the-carriage aspect to approaches to digital literature (in this case, mostly fiction) -- there seems to be this agreement that there has not been a truly successful (or universally applauded, i.e. outside of the immediate electronic lit culture) hyperlink-based work (i.e. successful in the way Hemingway was successful), but that it must be possible to use the link and higher forms of "interactivity" -- such as user influenced plot outcomes -- simply because the technology is available. My tendency is to think of it this way: yes, it's possible, but it's also possible that people speaking English could decide not to use case forms simply because they are superfluous, or invent new verb tenses simply because they use them in other cultures--so we know its supportable by our language faculty--but we've not found a need to do so and forcing such switches has never been successful in the past.

Perhaps it's possible that literature will never find room for user-influenced textual adventures -- perhaps, in fact, one reads specifically because it is the one time in one's life when one is not having to make choices involving the outcome of a narrative -- the one time an individual is not a writer. Of course game worlds would seem to contradict this, but that's why they are called "games." Well, this is all clumsily phrased -- I don't want to write off a venture with which in fact I have great sympathy. Certainly, I'm interested in "interactive" literature of this sort, but I think that the focus should not be on the presence of loops and control structures in a fictional work--or whatever it is a machine adds--but how one can (for example) inject ethical dimensions to the choices one makes in such a work, hence raising the art to the level that, say, Dostoyevsky did when he asked us to imagine murder as the solution to some existential puzzle. Maybe a more fruitful approach would be to think of all the added elements of interactive textuality as flaws and detriments--it's a bug not a feature approach.

I discovered the blog by looking at the new module from Stephen's Web ~ Referrer System which shows all the places from which people have followed links to get here. (Scroll down below my archives lists to see it.) I recommend it to you bloggers out there if you want to know whose visiting and how.

[Here's a little piece of writing I did several years ago, I think "pre 9/11," for a Swedish journal, OEI. I probably wouldn't have used the poets names that I used in this statement had I spent more than an hour writing it, but so it goes. In general, it's still what I feel, though only the skeleton of the way I would express it now. All of the English language statements that were submitted to this issue of OEI can be found at www.ubu.com/papers -- very worth glancing at. Writers include: Christian Bök, Stgacy Doris, Peter Gizzi, Kenneth Goldsmith, Karen Mac Cormack, Jennifer Moxley, Jena Osman, Juliana Spahr, Chet Wiener. The questions were: "How do you conceive of innovative poetry in America after Language poetry?" and "How do you define your own relationship to Language Poetry?"

My apologies once again for posting this reheated slop but I feel this obligation to the "feed the blog" and yet, once again, don't have any time to write anything new. I don't think anyone read this outside of Sweden anyway...]

My own sense is that there has been neither a smooth transition from the paradigm of "language poetry" nor has there been a "clean break" with it. There are several younger writers who wish language poetry never happened, some who believe that the tenets of language poetry are still the best thing going, and some who are picking and choosing from among the ideas that language poetry put forward and trying to reconcile these with more traditional poetic values.

There are several reasons for this. One is that, even when Language poetry was most in the ascdendant, there were still strong strands in experimental work that didn't owe anything to their theories or work. Some writers, like Susan Howe, are considered "Language poets" even though her work shares little with the work of the main figures, while other writers, such as Eileen Myles and the ever-productive John Ashbery, were putting out strong work that didn't owe anything to them.

Also, it never had the grip on the public imagination that, say, Beat Poetry had, probably because it lacked any "lifestyle" element -- no costumes, no drugs -- and because it had a fairly technical, and not humanistic, approach to poetic value. It was a highly self-conscious movement which often put forward a very methodical way of writing, and American poets by nature tend to disavow this kind of self-consciousness since it conflicts with a sort of romantic liberatarian attitude that believes the poet is a free thinker and a "witness to events" who is also, as an act of rebellion perhaps, an improvisational writer.

I'm being reductive here, of course, but this is an element that runs from Whitman (who was, to a degree, in conflict with the methodical, continentally-inflected writings of William Cullen Bryant) through the Beats to Ann Waldman and the late A.R. Ammons. It's not a viewpoint to which I'm entirely unsympathetic.

Language poetry is also often seen as elitist because it never dealt adequately with issues of race, gender, and sexuality, at least as a whole. Since one of its early premises was the critique of "identity" and the self, it never had the language for dealing with minority issues that attempted to legitimize "identity" as a central subject of discourse. As a result, there was a sense of haughtiness on the part of the Language poets who didn't want to "stoop to that level," though recently there have been more attempts by Language poets to incorporate these issues. Not suprisingly, most of the Language poets -- certainly of the first generations -- are of European descent (which is to say, "white").

So what that leaves is a poetic past that seems at once finished, incomplete, still lingering, in its death throes, yet more relevant than ever. Several mainstream writers have made their career marks by incorporating Language methods in their work, for better or worse, and it's sort of become hip again in some quarters.

As for me, I've spent a lot of time imitating the works of writers I admire -- from Ezra Pound to Charles Bernstein -- and have always been interested in trying everything possible to write a poem. There are a huge amount of formal explorations that the Language poets have made, and I certainly identify strongly with this impetus toward radical new methods. However, I've also been interested in writers the Language poets never took under their wings (usually non-Americans, like Ian Hamilton Finlay, Haroldo de Campos, etc., or not "avant-garde" like Martin Johnston, an Australian), and have tended to want to avoid the American-centric, Oedipal attitudes -- WE are the next big generation -- that have marred some of their approach.

As I suggested above, I'm much more interested in the idea of the poet as cultural agent and "witness", of a reinvestigation of some of those "libertarian" poetics attitudes (and am avoiding the academy at all costs), as well as a reconciliation of my own specificity as an Asian American writer with the more theoretical, methodical, post-humanist aspects of the group.

I've moved very much into digital technology with my work. Most of my most ambitious projects have been for the internet (they appear at www.ubu.com). "The Dreamlife of Letters," for example, is a long Flash piece that owes a big debt to Brazilian concrete (it's my love letter to that country), and my new piece, "The Truth Interview," a collaboration with the poet Kim Rosenfield, is not a poem at all but a collage of animated texts, an interview/profile of Rosenfield, a sort of "web portal," and travesties of common web phenomena such as the pop-up box advertisement and the subliminal sexual ploys in web imagery.

I also deal with "avatars," having written a long sequence in the voice of someone named "Roger Pellett." Though these are traditional "poems" -- words on a page -- I somehow attribute them to the anonymity that is natural to web culture, and is an open field for play.

I think my work is a direct descendant of that of the Language poets, but because of this attention to digital culture, I am more prone to see text as "data" and even less as the autonomous art-works and sanctified language that Language poets themselves once criticized, and yet for the most part didn't overcome or replace with new attitudes. My closest peers in this effort have been those centered around the ubu chat group -- Darren Wershler-Henry, Kenneth Goldsmith, etc. -- but since I live in New York, I am in constant contact with writers of many stripes, and hope to steal from them also.

My hope is that my work will remain public, like the way graffitti is public, and will never be marred by a critic's misguided attempt to place it back into the box of continental Modernism.

I was just reading the The Complete History of Hacking and came across this line:

[1981] Commodore Business Machines starts shipping the VIC-20 home computer. It features a 6502 microprocessor, 8 colors and a 61-key keyboard. Screen columns are limited to 22 characters. The product is manufactured in West Germany and sells in the U.S. for just under $300.

I had one of these... I still have all of the cassette tapes with my programs on them. I also bought the 16k expansion cartridge (the computer shipped with 2k), but never graduated to the Commodore 64, which I think programmers slightly younger than I am all had. I tend to think that it was the necessity to write very small, airtight programs that made the Pound dogma in "Dos and Donts of an Imagist" -- "use no word that does not contribute directly to the presentation of the thing" for example -- so attractive to me when I was very young (that and the belief that nobody reads poetry). What doesn't appear in the above Complete History is the appearance of my very first computer, the Sinclair ZX81:

I found this specs sheet on one of those ZX81 hobbyist pages, ZX81 Home Page. I can't believe people still like to program in this thing, since the programs disappeared every time you shut the machine off and had to be rewritten -- at least that's how I remember it, or maybe I didn't feel like it was worth purchasing the cassette drive.

Integrated Circuits

Z80A Microprocessor clocked at 3.25MHz.

1K RAM, expandable to 16K, 32K or 56K.

8K ROM containing BASIC.

A single ULA for all I/O functions.

Ports

Bus connector for adding peripherals.

3.5mm cassette tape interface for loading/saving programs.

UHF output for display on a TV set.

9v DC power supply. Smoothed down to 5v.

40 key touchpad keyboard.

Screen Resolution

32x24 Text.

64x48 'graphics'.

256x192 Hi-Res graphics. (But see notes.)

Various overscan modes. (Since it's only outputting to a TV set.)

Memory Map:

0-8K BASIC ROM.

8-16K Shadow of BASIC ROM. Can be disabled by 64K RAM pack.

16K-17K Area occupied by 1K of onboard RAM. Disabled by RAM packs.

16K-32K Area occupied by 16K RAM pack.

8K-64K Area occupied by 64K RAM pack.

Wow, what a monster. I don't know how I got this computer -- I think my father got it free when he subscribed to Time magazine or something -- but I bought the Vic 20 with the money I got from winning a TV trivia contest hosted by our local newspaper, The Herald News. I heard John Ashbery was some sort of trivia whiz kid, so I'm not so embarrassed to reveal that part of my early youth was spent involuntarily memorizing the names of the actors in The Munsters.

Following is a link to a German essay by Sylvia Egger (not the one who wrote the hearbreaking work of genius or whatever the f*ck it's called) about the "Creep" poets -- my German's quite crappy at this point but I've been promised a translation sometime soon... Sylvia had edited a special issue of the magazine "Perspektive" that was focused on the avant-garde under net conditions. I don't know how many USAmerican poets were involved beyond myself and Rodrigo Toscano. My contribution can be found here auf Deutch (of course, I wrote it in Engllish). I probably posted the English version to this blog some time ago... maybe not. I'll see if I can find it.

avantgarde / under / net / conditions